Documentation

Ethics of AI-art: A Case Study of Lensa – Rupsa Nag

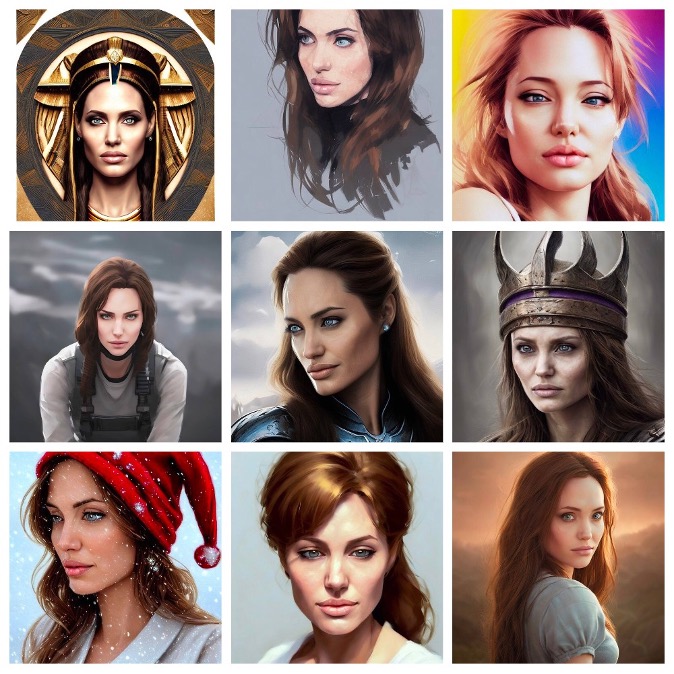

Lensa, by Prisma Lab, source: Wikimedia Commons

The seminar on ‘Social Imaginaries of Ethics and AI’ made us think through how Artificial Intelligence is imagined by its makers, its social implications and ethics. Through discussions on various aspects of AI, one that came up was the use of AI in art. This was a very interesting discussion considering the recent popularity of Lensa, the AI art-generating application being used by users across social media.

During the group discussions we were asked to think along two axes of dystopian-utopian and pragmatic-speculative. The dystopian-speculative axis opens up an important perspective of not seeing AI as an agent of change but rather taking a speculative approach to understand the sociopolitical imaginaries it is bound to inhabit in a society structured by racialised gendered-ableist capitalism. The AI industry is dominated by white male perspectives that create tools impacting diverse groups of people.

So when the Lensa app generates hyper-sexualised images of women, thins down bodies, lightens skin, makes eyes bigger catering to white patriarchal beauty standards, it demands a critical inquiry into the social imagination of AI and how it is developed.

Owned by Prisma Labs, Lensa uses Stable Diffusion to generate images. Stable Diffusion is an open-source machine learning model that is trained by feeding it publicly available images through which it learns to mimic various artistic styles. Thus, when a user uploads their photographs on Lensa, it uses the different artistic styles Stable Diffusion is trained in to generate the AI ‘magic avatar’ of the user. The images are therefore a melange of the user’s photograph with existing artworks. Artists have raised concerns about the image-training process being unethical because the artworks are sourced without consent from the LAION-5B database that extracts publicly available images from across the internet like Google Images, DeviantArt, Getty Images, Pinterest. The artists whose artworks are used by Lensa, a paid application, are not paid. Moreover, the training dataset has more than simply artworks since artists have found medical record photographs, stolen nonconsensual porn, photoshopped celebrity porn as well. This forms a major privacy concern of AI where there is no way of knowing if someone’s image has been added or deleted and if someone finds their image there they cannot take it down so even when users are uploading their images.

With AI’s exponential growth and entanglement with the world as we know it, we still lack clarity about AI datasets and there is no provision for accountability of abusive images these datasets might contain. In a world where visuality plays such a huge role in shaping our perception of the world and ourselves, there must be a deeper questioning of the racist, gendered violence built into AI itself. AI can most definitely be used for good, but technology must be understood not simply as a tool but as cultural objects because they are part of the construction of social life and meaning. Technology is something we make meaning of in terms of our location because the digital is material despite being presented to us intangibly, it has very tangible implications. And it is through our bodies that these technologies are embedded in our everyday life thus critically examining data computation and operationalisation determines what AI technologies are trying to do with said ‘data’. Thus, concerns about AI-art are to address the visuality it produces and how thereby unfolding AI imaginaries and where its narratives, metaphors and aspirations lie and what are the kinds of sociopolitical manipulations that have come out of it.

Bibliography

Weekman, Kelsey. 2022. “People Have Raised Serious Concerns About The AI Art App That’s All Over Your Instagram Feed.” BuzzFeed News. December 8, 2022. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/kelseyweekman/ai-art-app-lensa-instagram-photo-trend-problems.

Xiang, Chloe. 2022. “AI Is Probably Using Your Images and It’s Not Easy to Opt Out.” VICE. September 26, 2022. https://www.vice.com/en/article/3ad58k/ai-is-probably-using-your-images-and-its-not-easy-to-opt-out.

Edwards, Benj. 2022. “Artist Finds Private Medical Record Photos in Popular AI Training Data Set.” Ars Technica. September 21, 2022. https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2022/09/artist-finds-private-medical-record-photos-in-popular-ai-training-data-set/.

Xiang, Chloe. 2022. “ISIS Executions and Non-Consensual Porn Are Powering AI Art.” VICE. September 21, 2022. https://www.vice.com/en/article/93ad75/isis-executions-and-non-consensual-porn-are-powering-ai-art.