December

“Revisiting McLuhan’s temperature of media” – Max Peters

There is hardly any figure more prominently present in the academic discipline of media studies than Marshall McLuhan. His theories have shaped and cemented the study of media, and he stands out at as a creative mind who coined, created and analyzed terms and concepts for media. However, this does not mean that his theories are still widely accepted. On the contrary, there has been a significant amount of academic critique on several of McLuhan’s theories. As John Havick mentions, McLuhan’s writings were ‘not entirely accurate’, and his concepts were sometimes compounded by ‘unfortunate labels’[1]. One of the theories that has been often criticized or downright debunked is his conceptualization of media as either ‘hot’ or ‘cold’, or as I would call it, the ‘temperature’ of media. As Havick paraphrases, McLuhan’s temperature ideas come down to the following:

“Hot media supply considerable information for a single sense, leaving little for the recipient of a message to imagine; cool media offer less information, requiring the recipient to speculate about the details of the sensory message.”[2]

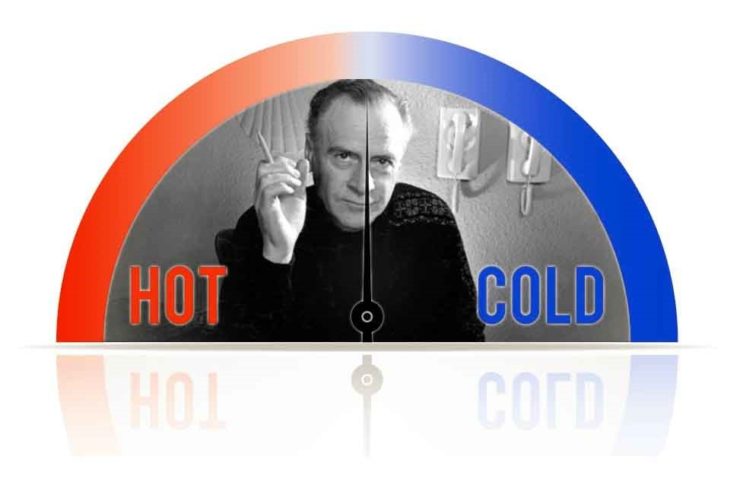

The first problem that arises with this theory is its binary opposition. Supposing that media are either ‘hot’ or ‘cold’ is limiting and deceiving, and almost automatically leads to superficial information and classification. Having addressed this important fallacy, this does not automatically imply that the theory is completely useless. In my opinion, the temperature theory has a certain use if we transform it from binary oppositions to a sliding scale. A scale between hot and cold, that allows us to recognize a certain degree of imagination and speculation on a particular medium. A medium is not either hot or cold, it can have elements of both. I think it is still true in contemporary media culture that the information provided for the senses can vary in its details and completeness. What is essential to add to McLuhan’s theory, however, is a medium’s ability to vary, or even play with its temperature. For example, McLuhan argues that an animated cartoon is low-resolution, and therefore a ‘cold’ medium, as opposed to the high-definition, ‘hot’ medium of photography. This classification seems outdated, but if we assess animation on the sliding scale of temperature, it becomes clear that animated films and cartoons can choose various strategies and styles, which determine to what degree they are ‘hot’ or ‘cold’. The photorealistic animation of, for example, Pixar movies can be considered ‘hot’ (figure 1), whereas the more simplistic, abstract approach of the Toccata In Fugue section of Fantasia leaves much more to the imagination, and can be considered ‘cold’ (figure 2). In other words, we could approach McLuhan’s temperature theory as a way to describe the quality and characteristics of a medium, if we leave the possibilities open for different temperatures within a medium. Therefore, I would say that this theory is not entirely problematic if we allow ourselves to transform and adapt his original ideas.

Figure 1

Figure 2

[1] Havick, J. (2000). The impact of the Internet on a television-based society. Technology in Society, 22(2), 281.

[2] Ibid.

References

- Havick, J. (2000). The impact of the Internet on a television-based society. Technology in Society, 22(2), 273-287.

- Lecture by Frank Kessler for the Transmission in Motion program on December 13, 2017.

Pictures from Disney-Pixar’s Coco (2017) and Disney’s Fantasia (1940).