Documentation

“What Is the Role of Digital Play in the Future of Education?” – Dennis Jansen

The question that makes the title of this post is one that has been around for quite a while. Already in 2003, when the field of game studies was only just beginning to find its feet, James Paul Gee wrote What Video Games Have to Teach Us about Learning and Literacy, and many teachers and designers have already experimented with using games and other playful interactive media in the classroom. Games are supposedly more engaging and more motivating than textbooks, meaning that the students are ought to be more willing to learn if that learning experience is also ‘fun’. While there is some evidence that games can be beneficial to student motivation and such (cf. Huizenga 2017, 14–19), it is also safe to say that the medium of digital games is not inherently better suited to motivate learning than print textbooks are—especially not if we consider that the student is also supposed to actually learn something. After all, how is Minecraft going to teach me anything about physical geography, if my play experience consists entirely of killing monsters and building cool houses?

This is a key problem in educational gaming: where does the balance lie between ‘gameplay’ and learning, theory and practice, game goals and learning goals? Evidently, the teacher plays an important role in ensuring that the students take away the right lessons from the games they play (Huizenga 2017, 108), but that is not the whole story. How can we create the games themselves in such a way that they convey knowledge, of any kind?

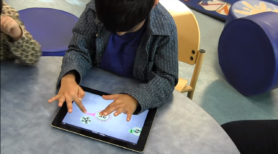

Usually, when we think of ‘knowledge being conveyed’, we mean theory-based knowledge of subjects like geography, and mathematics. However, during Nathalie Sinclair’s recent lecture on “Multiplication as Experience: Whitehead, Aesthetics and Gesture-based, Touchscreen Technology”, I saw an entirely different take on the kinds of knowledge that playful media can bring to the classroom. She demonstrated the TouchTimes app, a version of TouchCounts (Sinclair and Jackiw 2011) which focuses on multiplication instead of addition/subtraction, and argued that the preschool children engaging with the app were gaining a sort of playful feeling for the concept of multiplication (see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T9VNuacbwZM). Sinclair’s app is not merely a mediator between students and the mathematical concept, but a tool that allows for new material, embodied conceptualizations of multiplication. Rather than creating any theoretical understanding of what it means to do basic mathematical exercises or solve basic functions, the players of TouchTimes use hand gestures to perform multiplication and to ‘get a feeling’ for abstract elements like the two-sidedness of multiplication functions and the transformation of numbers (see fig. 1).

Figure 1: Playing with gestures and numbers (source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T9VNuacbwZM)

In a sense, these apps stand closer to games that teach the player skills like playing guitar or touch typing. Could we say that educational games should not focus on producing knowledge or motivation, but instead produce gesture-based and material relations between their users and the concepts they present? Perhaps this is an angle that would open up the possibility for games to truly come into their own as educational devices.

References

- Gee, James Paul. 2003. What Video Games Have to Teach Us about Learning and Literacy. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Huizenga, Jantina Catharina. 2017. “Digital Game-Based Learning in Secondary Education.” PhD dissertation, University of Amsterdam.

- Sinclair, Nathalie, and Nicholas Jackiw. 2011. TouchCounts. [iOS]. Tangible Mathematics Project, Simon Fraser University.

- “TouchCounts: Joy of playing with numbers”. Youtube Video, 2:54. TouchCounts 1.0. January 16, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T9VNuacbwZM.